I. committed to abstraction

I strive to stay attuned to my own sorrows and joys, and to express them in art that is drawn from that place of attunement. Using abstraction, I leave room for viewers to bring their own sorrows and joys to the interpretation of the work. Abstraction is the middleground where we can hopefully meet.

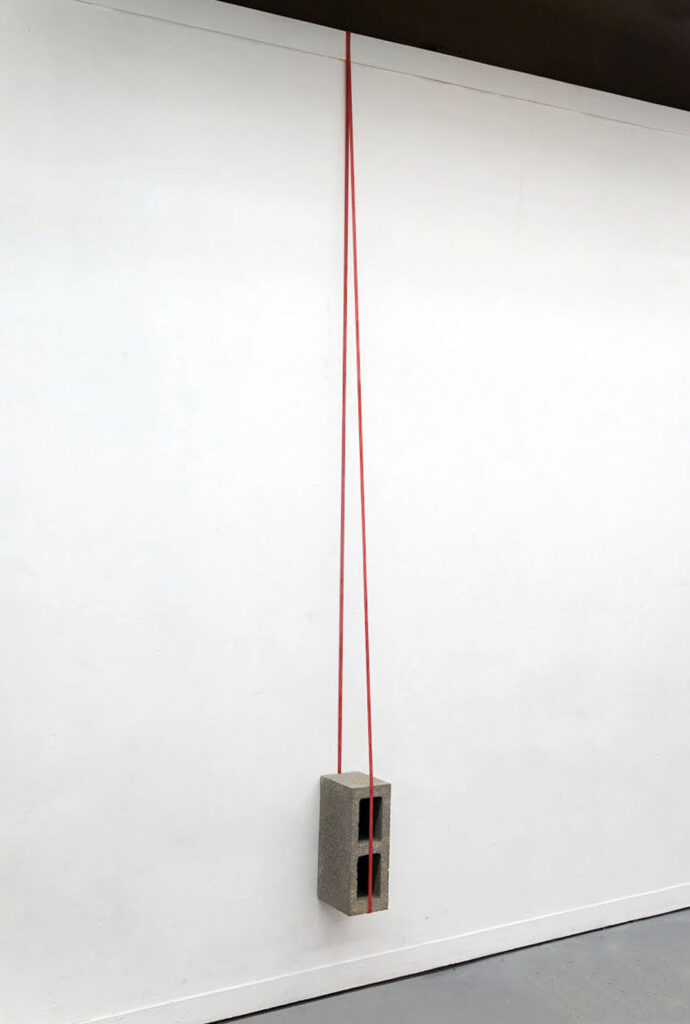

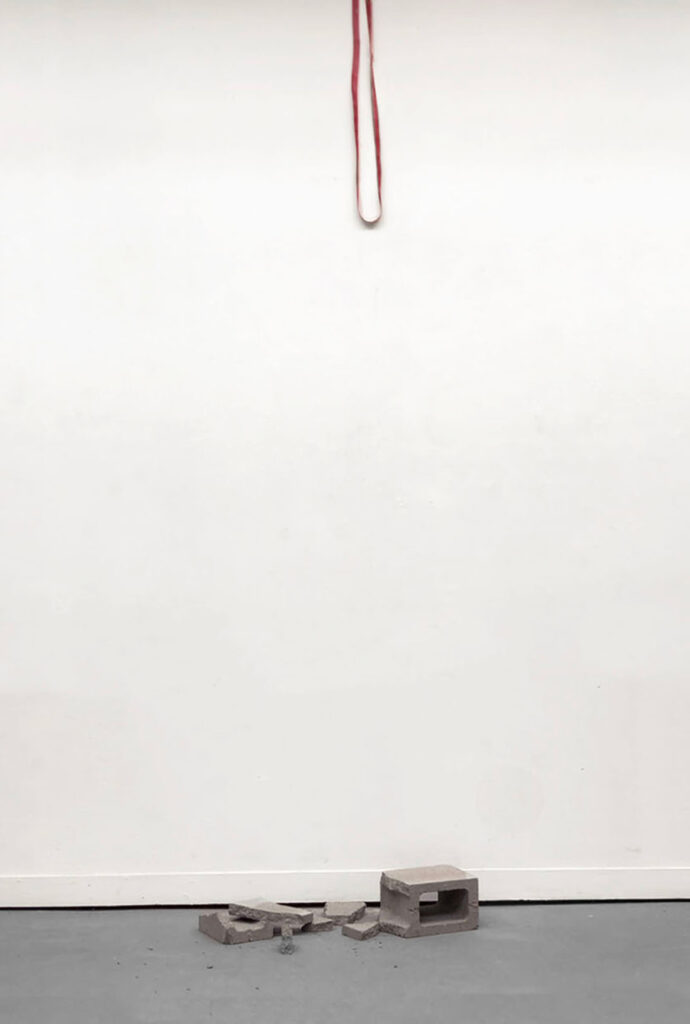

III. wait / weight (May 2021)

To start the process of healing, we need to allow for things to break.

In wait / weight, a cinder block held precariously by a packing band slowly lowers toward the ground. Due to the weight of the cinder block and the elasticity of the band, it eventually loses balance, falls to the ground, and breaks (usually over the course of four to six hours). As part of the work, I sweep the broken pieces and re-balance a new cinder block into the rubber band.

I make and remake the work only to let it fall and break apart again. By allowing for damage and loss to exist within a process-oriented ritual, my maintenance of the piece becomes a metaphor for

the cyclical efforts we put into healing, changing, and growing.

I can see by looking through the photo history on my cell phone that I started this piece on January 9th, 2020. At that time, I had just begun experimenting with tension and precarity and didn’t fully understand what these concepts meant to me. I had a lot of questions about this piece—some emotional, and others logistical: What is the personal and conceptual significance ofwait / weight? Could it be considered a kind of performance? Should I install photos of the work in different stages alongside the sculpture? Those questions swirled around in my head and remained unaswered for more than a year. It wasn’t until the spring of 2021 that I was able to contextualize this piece within a larger body of work, and could finally provide the formal and conceptual scaffolding that it needed.

That spring, amidst the enduring stress of Covid-19, I had planned a trip to Philadelphia to spend time with family—I hadn’t seen them in almost two years, and I missed them. But alongside my feeling of sincere excitement, I felt a familiar unease and apprehension building within me. Recently, I’d become more acquainted with my own feelings about family trauma, which were seldom mentioned, but still found ways to occupy valuable space in our lives.

Before the trip, and in preparation for a scheduled studio visit via Zoom, I went to school to document my work. While creating a video recording of the block falling to the ground and breaking, the personal significance of this piece suddenly occurred to me. As any artist might hope would be the case for an a/effective piece, I not only discovered something about the artwork, but also about myself. I barely slept that evening—though not for lack of trying—as I grappled with my new awareness.

Without exposing my family’s personal stories in detail, I want to acknowledge that much of my work—and this performance in particular—is an attempt toward (the idea of) healing generational traumas. It’s not important to me that viewers come to learn about or understand any particular life story, but it does feel important to recognize that my work stems from the depth of my personal experiences. It is equally, if not more important to me that viewers also feel encouraged, through interacting with my work, to bring their own life stories into the acts of seeing and engaging, and to discover a process of recognition and healing as a result.

III. bent out of shape (December 2021)

A wooden cart filled with bricks and cinder blocks sits collapsed under the weight of what it holds. Its red casters swivel in different directions and the bottom piece of plywood is bent in the shape of a smile touching the floor.

In the winter of 2019, I was in my first year of an MFA program at San Francisco State University. With this privileged gift of time, I began learning new skills such as laminating and bending wood. These processes were fun and messy and resulted in a substantial accumulation of clutter; I needed to find homes for the bits and pieces of wood that had taken over the surfaces of my studio. I hadn’t had any formal woodshop training, but if I could learn to bend wood, I felt that I could certainly build a simple cart: so I did just that. The resulting cart came to represent not only a structure for organizing physical objects, but also for holding and reflecting a growing sense of confidence and mental clarity for me about this new chapter of my art practice, and my life more broadly.

Fast forward to the spring of 2020: I was well into my second year of graduate school when I started hearing news about Covid-19. The World Health Organization declared this new virus a pandemic and soon after, school—along with many other aspects of my life—drastically changed course.

During the first few months of the pandemic, I felt preoccupied with worry and stress, and I struggled to find the significance of making art objects.

I worried most about my grandmother, whose resilience I had never before questioned. She had survived Nazi Germany, raised a family, started a small business, become a competitive rower, and actively participated in the Anti-Vietnam War Movement—but she was now, at this moment, confined to a single room in her nursing home. The only visitors allowed into her room were staff, who, wearing full medical gear, dropped off food and performed mandatory medical check-ins. I imagined how lonely she must have felt. Then, in September of 2020, she passed away. Somehow, this woman, my grandmother—with all of her strength and sensitivity—ended up alone during the last months and moments of her life.

Meanwhile, I had been experiencing the jarring new reality of Zoom school. I knew that everyone was trying their best, but live video chats could not replace person-to-person interactions. I sincerely missed the casual and intermittent conversations with peers and professors that happened so often in the pre-pandemic version of graduate school. I thought about taking time off, but knew that I was lucky to have the safety net and structure of school in a time when almost everything felt uncertain.

In hindsight, I realize that though my pandemic grad school experience oftentimes felt painful and lonely, it pushed me to trust myself. While I desperately missed comradery outside of computer screens, I learned to appreciate a newfound sense of quiet. I no longer had to juggle so many different opinions from peers and professors and found that my own voice had gotten a little bit louder; it had begun to take up more space.

Before the pandemic, I had only just begun to incorporate found objects into my practice. Working from home without access to the various, well-equipped shops I’d been accustomed to, I resorted to using more and more found objects—such as discarded bricks and cinder blocks. These materials, which had once delineated garden beds in my backyard now delineated an emotional landscape. The weight resonated with the emotional freight I had begun to feel during this strange time, marked by seemingly endless angst.

About a year into the pandemic, after the first round of vaccinations had rolled out, I made the decision to return to my studio at school; I felt both cautious and excited as I loaded materials into a friend’s van. In the span of one afternoon, I carried about 600 pounds of bricks and cinder blocks one by one into my old space. With clarity about needing to make room for these new materials, I disassembled the aforementioned cart, discarding most of the wood scraps it carried but holding onto the frame and casters. Then, without thinking much about the physics of weight or gravity, I stacked the bricks and cinder blocks inside of the newly altered and recycled cart.

It remained stable for several weeks. One afternoon, however, I walked into my studio to find that the cart had collapsed. At first, I didn’t think much of it—but within a few days, something clicked. I realized that through the act of slowly falling apart, this cart mirrored exactly how I felt—stretched to my limits and anticipating some form of failure or disruption to provide much- needed relief. This, to me, was the perfect culmination of my time and journey with these found and repurposed objects.

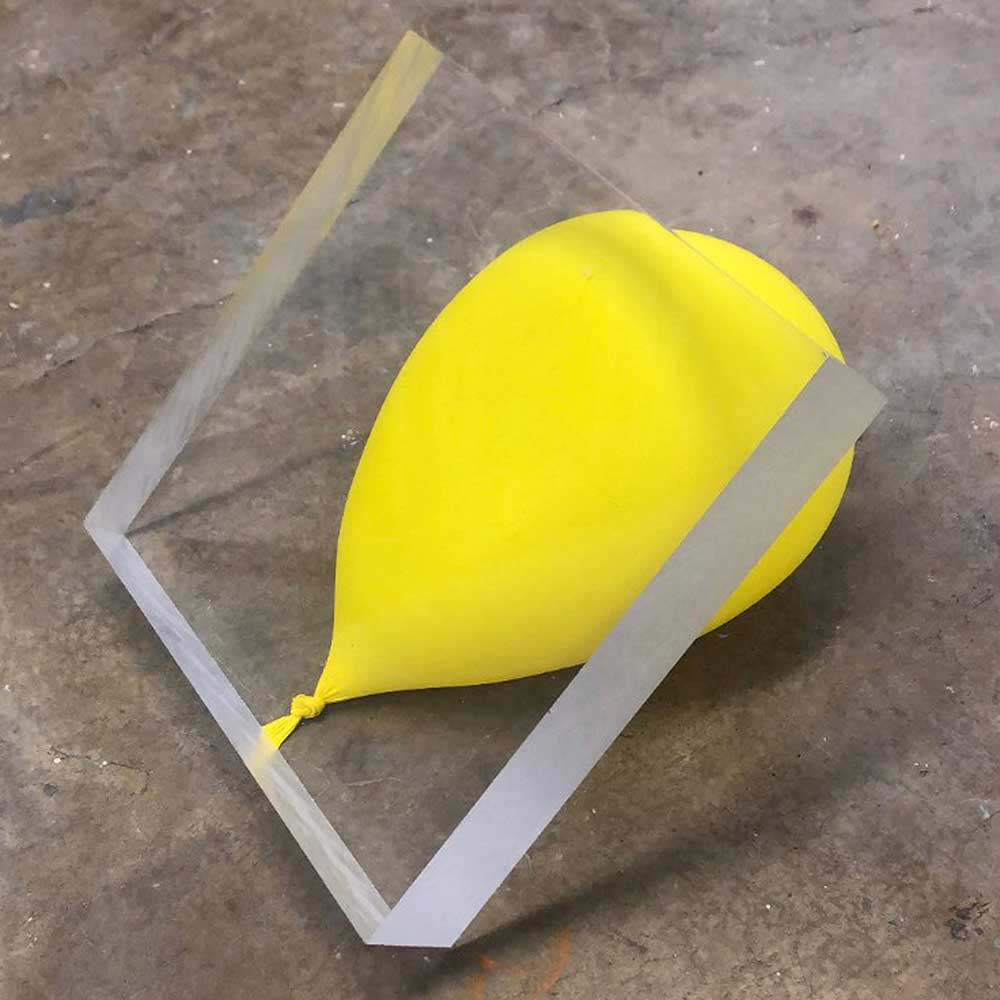

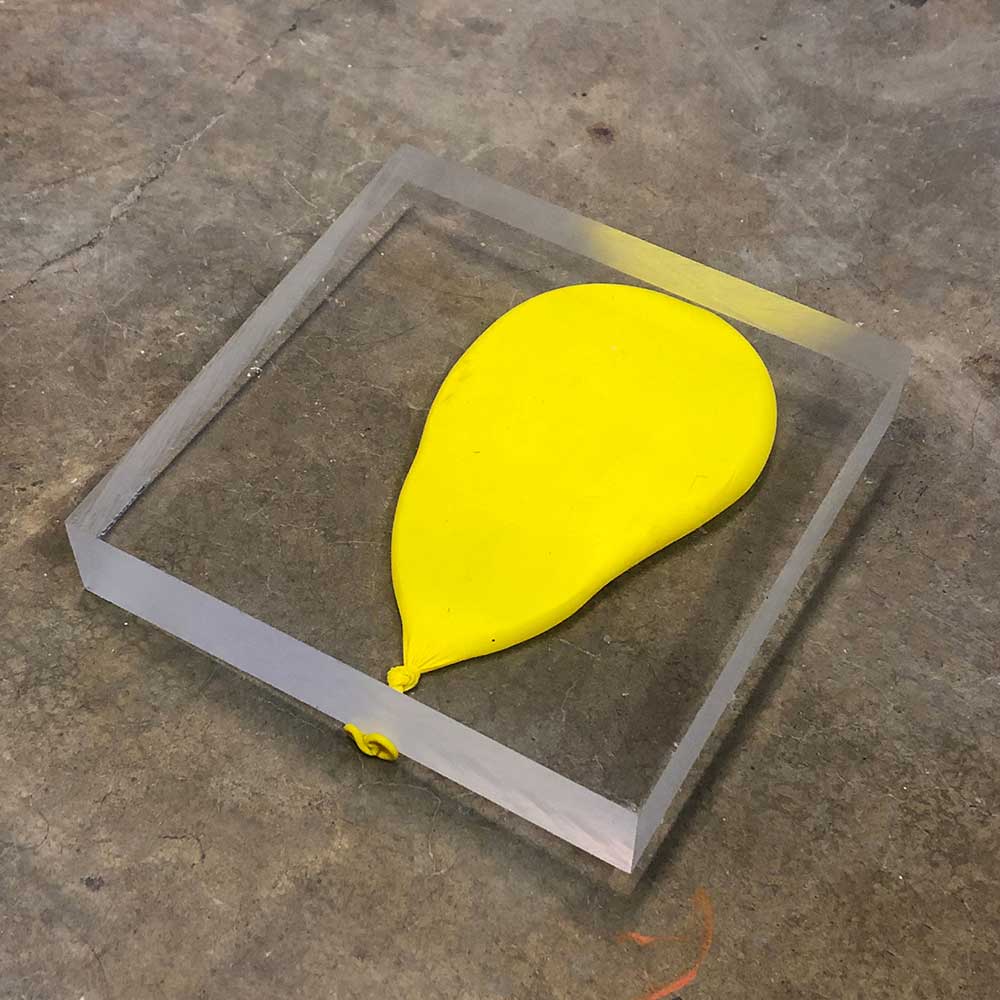

IV. pressing time (August–September 2022)

A large, yellow balloon slowly deflates under a fifty-pound piece of clear plexiglass, its weight both stabilizing and squishing the balloon. Seen through a window in the Outer Sunset neighborhood of San Francisco, viewers may have noticed subtle shifts in form throughout the duration of the exhibit. Through a language that accepts instability and the possibility of failure, this work expresses emotional weight, temporality, joy, and humor.

*

When John Lindsay, the owner and curator of The Great Highway, approached me via Instagram about exhibiting my work there, I was absolutely thrilled. Over the past year, I had popped into the Great Highway a handful of times. I was enamored by the space and the friendly atmosphere.

The evening before John sent me a message, I talked with a friend about the gallery and said that I wanted to see my work in that space. I remember specifically sharing that it felt important to say this out loud—and I hoped that in doing so, I could begin to turn some of my dreams into part of my reality. The serendipity felt significant; it felt like kismet.

Apart from my enthusiasm about this particular gallery, I was excited to install my art in a window for the first time. Sitting somewhere between a private and public space, the Great Highway is a small window front gallery in a neighborhood abound with coffee shops, bars, and cafes. For these reasons, I knew that I wanted the work to be appealing to a wide range of audiences, from casual pedestrians to art enthusiasts.

My choice in color for the balloon in this installation was especially deliberate. I’m drawn to the duality of yellow, a color often designated for both caution and delight; it is used to warn people of potential danger (e.g. traffic lights) while being simultaneously employed for depictions of things of a more cheerful nature, like smiley faces and the sun. For me, this duality supported an expression of joy and humor alongside an honest depiction of instability, temporality, and loss.

Prior to installing pressing time, I made a more intimate version of this piece in my studio with a party balloon and a small piece of plexiglass. When I substantially scaled it up, I felt excited by the shift in content and mood. The balloon, which became more abstract after growing in size, related in a different way to my own body. The slow release of air felt like a gentle exhale and a reminder that everything is in flux. It became a testament to our vulnerability and the impermanence of the present moment.

V. repairing watches (May 2023)

A variety of purple rubber bands in different shades and sizes are woven together and attached to the wall with small colorful map pins. By severing the bands, I interrupted their primary function, which is to hold things together. But by weaving them back together, I reconstructed them into an object of healing and hope. Over time, the woven rubber bands slowly deteriorate, inviting viewers to consider the inevitable instability of any material or structure without ongoing practices of maintenance and care.

In the summer of 2021, I got the news that my Uncle Billy, had been diagnosed with Glioblastoma; his prognosis was terrible. I felt devastated for his kids (my little cousins) who are more than a decade younger than me. He was sixty-one at the time.

Throughout his two years of treatment, he regularly wrote letters to his loved ones—family and friends alike—and I felt honored to be included in that list. My uncle had a gift with words; his descriptions were deft, poetic, and playful, and his voice permeated with humor and heart.

In November of 2022, I pinned one of his letters to my studio wall. The following spring, I started a series of rubber band weavings next to the letter. Somewhere during this time, he received hopeful news about his treatment. His tumor had been successfully removed, and he was even cleared to return to work. Coinciding with the rubber band weavings, I felt a palpable sense of repair. But, about a year and a half into his treatment, we received devastating news— due to the aggressive nature of this particular cancer, the tumor reemerged. As time went by, the rubber bands slowly deteriorated. And, so did my uncle’s health. He passed away in June of 2023.

When Uncle Billy was alive, he’d repaired watches for a living. Since his passing, I’ve thought a lot about his livelihood. He cared for devices that attempt to tell “time”—something elusive, defined by its own ephemerality. This work is dedicated to my uncle and to the passing of time.

A handwritten letter from my uncle hangs on my studio wall. A small piece of yellow tape holds it up.

Yellow lights remind us to slow down, to approach with care.

He folded the paper twice to fit it into an envelope.

These folds, now sculptural on my studio wall.

My uncle’s pill box reminds him of a typewriter keyboard. He wrote this on stationary from his mother-in-law’s violin repair shop—

reminding me that my grandmother repaired violins and my uncle repaired watches.

Woven rubber bands pinned onto my studio wall begin to harden and curl, revealing small cracks that weeks before could only be imagined.

The evening after his memorial service, a sun sets: I was not prepared to stop, to stand still, but I did.

From a photo on my phone dating back to last July, I can picture where I stood—

and how I still stand,

always somewhere in relation to a sinking sun.

I must have seen a streetlight then. One bulb lit, the other presumably broken.

A failing light, prompting me to slow down, to approach with care—

reminding me that my uncle repaired watches and my grandmother repaired violins.

VI. until now (September 2023–present)

Over time, I have come to understand that my artwork excites me the most when I have learned something new about how I feel through the process of making it. This realization has led me to developing intentional studio habits that directly relate to the produced piece. I view these habits, or rituals, as private performances, and the resulting work is tangible evidence of these performances. In until now, a current and in-progress project, I have committed to a repeated meditative act of silkscreening the common expression, “Everything has been leading up to this moment” onto individual sheets of paper.

Since finishing school, I have found it difficult to work full-time and maintain steady studio habits. One evening, as I was thinking about this, the expression, “Everything has been leading up to this moment” suddenly popped into my head. There was something both humorous and sincere about the sentiment. As I laughed, I quickly understood that I wanted to somehow incorporate this expression into my practice. After letting it mull around in my head for about a year, I decided that I would repeatedly silkscreen the phrase as a form of emotional self-maintenance—a private performance to remind myself of presence and impermanence.

While I don’t always have the time to completely immerse myself in an intensive studio process, I do have time for maintenance. This piece reminds me that every day, I have the opportunity to be present and partake in that maintenance.