I could talk your ear off about the current state of Mexican-American literature. I spent the first half of my life in public schools (good ones) in a suburb of Arizona learning almost nothing about it. Its absence felt like a wreckage — the evidence was so cleanly removed that its only walkable paths were on the periphery. And if something canonically acceptable did show up, I didn’t feel that shit. They had us read Bless Me Ultima and harped about how culturally significant it was, how beautifully exotic. There wasn’t much to figure out — the way the teacher taught it and how the discourse unfolded was as if Mexicans were lesser. I was one, but I had papers — those without them were living a life I had to keep far away from, even if everyone was employing paisas, who they called wetbacks and day laborers and cleaning ladies, the men and women from my parents’ country. I went to school with their kids until I was placed in an advanced program and bussed off to the white school.

I should have studied Mexican-American literature in college. But I was too busy. Working at hotels and traveling and reading detective novels alongside Dostoevsky and Toni Morrison. Took me years to figure out that I was already living in a similar story to those that I loved: an unlikeable and slightly arrogant narrator on some sort of pathetic Odyssey; a slow-ass journey back to myself, to my people or history or context. The desert where my dead are buried. The only book I finished in high school was Song of Solomon and it’s still ringing through me, I think. I often feel like its protagonist Milkman Dead (the great characters never die, their stories don’t stop) driving through the night of this country, discovering great omissions, old truths that weren’t true at all; lies I once thought were true.

My mother was from Ciudad Juárez and my father from South Phoenix (which might as well have been another country). All their family were either here (here being Arizona and the Sonoran desert and its sprawling, connected cities, so much former farmland stolen from 21 tribes) or dead.

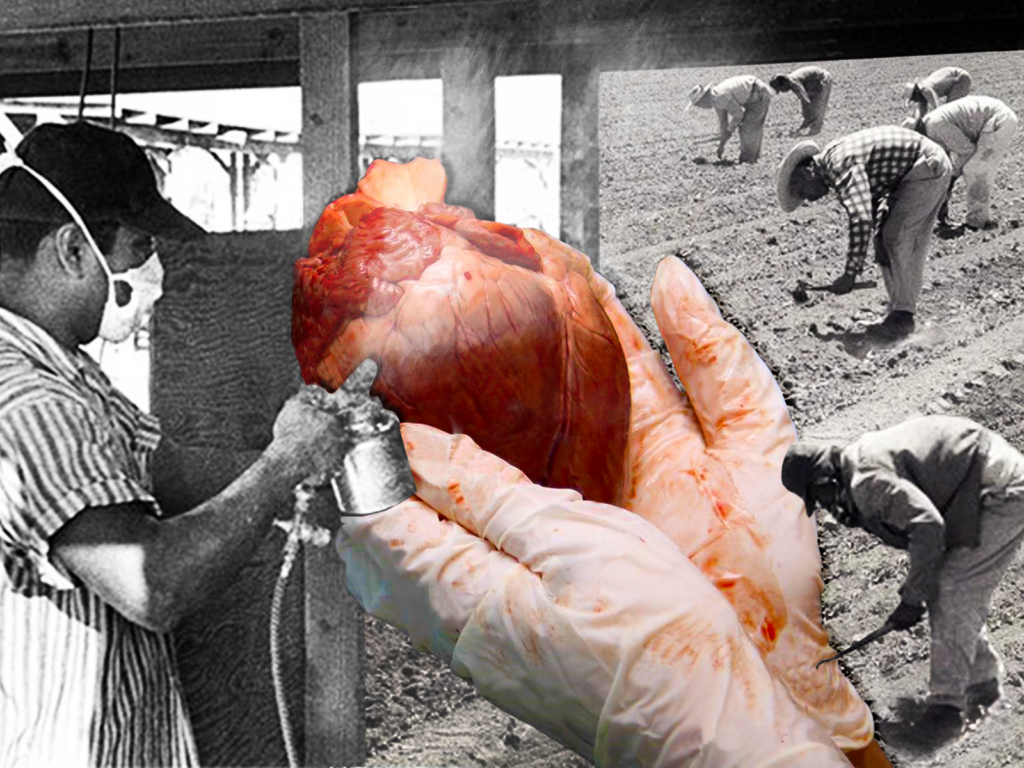

By the time I came around, there was no more crossing, no more going back. Two of my grandparents died before I was born, and the remaining two I barely remember. Instead of them I have vague facts: my grandfather on my mom’s side was a Bracero worker; the other one was an alcoholic, but a kind and funny one. My dad’s mom died quickly and tragically before I was born; her fact was that she deeply loved my mom, maybe the only woman on his side that did. My mom’s mom, my abuela, died when I was four or five; she is only feeling to me, physical memories like waking up in her bed when my parents vacationed or had a night out, slamming the screen door of her larger-than-life kitchen, peeling off the cicada skins from the trees of her house. My parents met at a town dance (which seems otherworldly, these taxpayer-funded community dances and two young Mexicans finding each other there). My father was simply dressed as what he was: a Chicano marine. My mother was beautiful, a Norteño Cher.

I was ten when my father unexpectedly died just a few weeks after my aunt, my mother’s sister and best friend, did. Him from an aneurism of the aorta, her from a long battle against cancer, both I suspect connected to growing up Mexican-American in the Southwest. After that month of funerals, I only saw my mom in snippets. She didn’t leave her room for a year. I grew apart from my three sisters, newly tasked with raising me. I stopped engaging with the many structures and routines that had made up my life: school, church, sports. I know now that my trouble swallowing food (every bite washed down) was a profound external reaction to the internal reality I couldn’t face, wouldn’t face, for many years.

A year later I would gather money from my friends, pack up some clothes and a sword I bought from the Renaissance fair to begin a new journey to Las Vegas. I ran away; I made it halfway to the Greyhound station before my mom and uncle found me. I was being swallowed by the narrative of my life.

Two years later, I was sitting in art class thinking about the pottery assignment I was surely going to fail because of ditching so much when my teacher came into the classroom and turned on the TV, saying nothing to us. The second airliner entered the World Trade Center like a toy and people tumbled into the sky. The scene replayed, zoomed in. She turned it off, spoke some words that I’ve since forgotten, and we began our assignments. That day, 2,700 people would die, war would begin, and we started hearing a new story about America. I mention this because I’m interested in grief, the space between public and private, or history and memory. How to sound all of that out.

My father’s death has taken on a political, historical tint in the years since he died: his heart’s aneurism was likely caused by contact with Agent Orange as a young Mexican-American in the Vietnam War. His absence, of course, shattered us. My mom, the strongest survivor I know, eventually recovered and doubled-down on our assimilation. Learning Spanish, her mother tongue, was seen as a joke, a waste of time. None of us had the tools to see how unhealthy or unfair this was. I, like many around me, didn’t even know what the Chicano movement was. My home never showed us ourselves, never explained what happened, how we got here, the land that was once ours, didn’t explicate shit. The absence presented a void waiting to be filled. This was how hip-hop found me.

Every song that I loved (and I’d play them hundreds of times) was a boat ferrying me back to language. If you were any combination of a 90s kid in a city and a person of color and remotely interested in poetry, Nas’s Illmatic changed everything. I listened to this in between Pennywise and Radiohead and felt its sublime lyricism stick out like a beautiful skyscraper, a city line forcing me to look up and then around. The images were gigantic, seamless, and perfectly his. Illmatic was the Pedro Páramo to the hip-hop that would follow. Listening to songs like “The Genesis” and “The World is Yours” gave me a lyrical map — a sound, a guide for how to piece together, narratively and sonically and politically — a life that could describe itself from the margins.

Hip-hop gave me meaning, privately held meaning, to a soul that didn’t want to be here after the surest and main thing in my life, my dad, had his heart fall apart from being American and brown. It was preventable. That was the hardest fucking thing. The doctor should have given him a CT scan but it was a Friday, a three-day weekend, and the doctor had a vacation to go on. Maybe this would have altered the puzzle pieces of my father’s end if that doctor hadn’t been white. I didn’t want to work at all after I saw him, the hardest worker I’d known, go out like that. Didn’t want to show up. It was easy to fail, and I wanted that ease. It was hard to figure out why.

I’d won a poetry contest in elementary school with some appropriately sentimental thing that rhymed about how much I loved libraries. Imagine Shel Silverstein doing Borges. I was obsessed with language, with the sound of it, the history of words, the sonic slipping into resonance. But after meeting death, and its silence, I wanted nothing to do with sound or meaning. All language, even my own interior, became obscure to me, its own dead thing. But hip-hop brought it back, slowly, something that was mine, in my earbuds, this replayable art that was so incredibly alive and modern and dangerous that I had to work to understand.

Context is everything for hip-hop; it’s always referential, it builds and reworks sound constantly. Its poses and jests come from the street and the conversations whirling through America. It’s Black and its Blackness is inseparable from it. I think it’s easy to forget how revolutionary and counter-cultural hip-hop was. It was both powerful and against the powers of this country. And it utterly conquered. When I was young I read about Hannibal crossing the Himalaya with elephants; what felt more real and modern to me was Tupac giving interviews about running through the streets blasting and then switching or connecting that with how many went hungry in this country. I, and those around me, didn’t need Shakespeare because we had Nas and RZA and Bizmarkie and Biggie. If the Bard himself were here, he wouldn’t be reading any of his own shit; he’d be obsessed with the Fugee’s fallout and Lauryn Hill’s irresistibly beautiful rise from what that did to her. Maybe I could have understood those kings and iambic confrontations and felt his brilliant dramatic flourishes but they didn’t enact for me a fraction of what rap made me feel.

You cannot understand America without some understanding, appreciation, or at least fear of hip-hop. If you’re indifferent to hip-hop, I think you’re fucked. You missed out on the 90s and your teenage years and the people across your street and your old flame who will never call you. Being untouched or unaware of hip-hop is like waking up missing two or three of your senses and being fine with it.

What was hip-hop? It was like a revolution that didn’t sell out — it had its murdered heroes, its martyrs. Its currents that moved its artists felt both oppositional and inviting. Its materialism always felt like jokes against the materialism that was all around us: mirrors, both private and public. Its misogyny felt more honest than any locker room or classroom. It was voice turned into percussion, cadence into sequential story. It was building a national grammar that was counter-national.

And if you study and listen to hip-hop enough, if you keep digging deeper and deeper to its roots, you’re exposed to Black writers. For a young, impressionable Mexican-American, one who felt that so much of what I was told was history and greatness and foundational were lies, Black writers and Black intellectuals were essential to how I understood America.

Rap smuggled a truer understanding back to me, in my earbuds, and directed me to the library. I had to figure out so much shit on my own, but the artistry of hip-hop, the creation out of nothing, the remixing, the come-up, enticed me forward. I learned about the backbreaking labor extracted from farmworkers and millions of Latinos in this country, and before them, in silver mines and sugar fields in New Spain. The genocide we’ve built our society on. I could understand my people’s erasure from canons and street names and history books and official languages and Hollywood in that light.

I learned how Black Mexico is, how our diaspora was connected to Mestizaje, and that Indigenous people were not extinct, but a people in history just like the rest of us. It allowed me to take a stand, somewhere. Had to double-take on relatives telling me not to date the Black girl in my class, or even hang around her. And to reconcile that fact with my grandparents’ sacrifices to get us here and then learn almost nothing about ourselves. It was a detective novel, an Odyssey.

It was enough for me to suspect that there was something incredibly broken about how America saw me and how it saw itself.

I was told, growing up, that I wasn’t allowed to be mediocre. This is common for anyone who lacks privilege, i.e. anyone not white and male and cis, in this country. Even if this is largely left unsaid, it’s lived. It’s the contours of making it in this country and paying your bills. The constant: be better. The assumption under that? There is no safety net if you don’t rise above others who look like you — those who are also navigating these corridors and levers of upward mobility.

This fact was made real and racial when I was six. We’d moved to the suburbs (the edge of them, really). I started school. I went to the building and sat at the desks and met my teacher and played on the playground. Everyone was brown; English and Spanish were equally thrown around.

Three days later, my father pulled me out of the school because they didn’t have the mandatory “gifted program” testing. I took a long ass test at some other nicer school and that was it. My days then began at 6 a.m. to catch the bus to go to that school on the other side of the suburbs. And I must have learned that freedom, for me, meant forsaking my community. Not finding myself through them, but forgetting them, so that I could succeed.

After a disastrous decade of not attending class, arguing with teachers (the most memorable was a tiny, raging white woman yelling at me in front of the class, demanding to know if I thought I was smarter than her) and running away from the ones who genuinely cared, I managed to graduate college.

This was how Hamilton the Musical found me the first time.

I’m not one of those people who expected a history dissertation from Hamilton. I’m not even sure I learned anything new. It was all about the slant, the angle, the sound, the grammar of hip-hop telling this old, official story. (It felt dangerous when they publicly announced that white people need not apply for its roles. Exciting, too — symbolic, and a little funny.)

I don’t need to go into the brilliance and the problems with Hamilton. Many better have already done so. Ishmael Reed, especially. And beyond what’s written about it, that same conundrum exists for anyone who is a person of color in this American Empire — we must reconcile the advantages it gives us with its dangers to Black and brown bodies, with its lies which are often official and its promises which are often lies. To live here and do life in America is to be entertained, brilliant, and highly problematic.

The first and most glaring problem to me with the story America tells about itself (and what Hamilton bandies) might be the American promise of progress. A lie has to be specific, provide some semblance of logic; it is paint but a paint that doesn’t stick or blend together. Here’s a truth: I never liked those 1920s parties, the Gatsby-esque décor, the bad outfits and worse alcohol. But more than the aesthetic, it was the reality under the veneer that got me: if I truly was in 1920s America, I wouldn’t be at a party. I’d be in the field, exhausted and broke. I might be deported or repatriated, even though I was born here. If I were in Texas or Arizona there’d be a definite possibility that I’d be hung on a tree. My family doesn’t like when I talk about these historical realities (especially on holidays). Call this progress.

White people used to send each other postcards of lynchings with a crowd of them posing next to murdered Black bodies. Now, we can watch these murders in real time, on Facebook, looped and debated and shared. Those postcards stopped being sent because that terror left the privacy of white people’s hands and the fields and the dark nights and has instead been brought out into the public square.

This is where Hamilton the Musical has found me today. Wondering about what is undergirding the story it’s telling us.

I hate calling myself a writer, or even a storyteller — especially when introducing myself to strangers. It usually begs the question from those I tell as to why my novel isn’t out yet in the world, or prompts them to tell me about one they’re trying to write in their spare time. These conversations never speak to how one is supposed to get a narrative told — how to find the shape of it, including what to leave out, what to fail to speak on, and how to bring it into the world — even though this is the real work of writing. It isn’t putting pen to paper or finger to keyboard, but incorporating better context, figuring out what lies beyond its ending as it begins in the minds of your readers. It’s about the conversation your novel is having with other novels, ideas, and writers in the world (and hopefully with you).

What Hamilton aims to do is tell us a story about both our origins and where we are going. Lin-Manuel is a child of immigrants, a brilliant brown theater kid who seemed to have found the lane to American success, after all. He’s said something to America, about America. From the first song in the musical, we’re expected to feel sympathy for the Founding Father. But the true story of Hamilton’s life tells a very different story, perhaps one that isn’t sympathetic at all. He bought, and very likely owned, enslaved people. He married into Schuyler wealth that was assuredly built on and through enslaving people. Lin-Manuel didn’t exactly write songs about this. But how big and how gravitational are these omissions? Fiction and works of art might be made-up, organized lies, but what happens when the heart of it is lying to us?

How will the story and the songs age? A major theme throughout the musical is legacy, but the most interesting legacy might be its own. Will it be looked back on as the start of a new, long-promised multicultural America? Or the fanfiction and origin stories of white supremacists? Do both of these realities or promises exist within the same body?

The comedian George Lopez got a lot of shit when he proclaimed that Mexican-Americans don’t really care about people who are detained and those without documents. But that hypocrisy and mendacity is stamped on our citizenship papers, on our IRS statements and our literary awards. It’s on my family’s upper middle-class status. It’s on everything I’m not giving and doing and being for the most vulnerable who had the audacity to come here, the hope that I take for granted daily. It’s in my earbuds as I’m singing along to Lin-Manuel as he sells this immigrant-ethos as the true origin story of America and I think of all the work, all the reading, all the contradiction flowing inside of me to realize that what was built by immigrants was built on genocide. And I think, also, of how many brown people often use Black art and Black people as a stepping stone to whiteness.

Some days I think the biggest problem is not with Lin-Manuel’s creation or even with the Founding Father himself. It’s with so much history untold, unfelt. It’s a problem of grammar, of silences. It’s the unnamed dead out in the field, the deserts, the creeks. These are a part of the musical, too, even if they’re omitted, because the musical claims to be telling the story of our collective foundation through this man, this immigrant.

We survive here, in this place, in unequal ways. The only thing shared might be our choice to live (how often this is weaponized, how often we are pitted against one another).

Alexander, conflated with Lin-Manuel on The Hamilton Mixtape, is primarily painted as a great writer, a builder of paragraphs and the nation. I felt my own story being told through the songs of his come-up and riffing on Nas’s One Mic, where he says all he needs is one page and one pen, my own goals and impossible dreams. Much of me is still that kid who loved libraries, who felt the word imagination was unfailing and incorruptible, that racism and genocide couldn’t possibly exist in that scope of dreaming, living, and building. Eudora Welty, who wrote fiction, said the writer has, always, the widest possible theme ready for them and that it’s simply this: “you and me, you and me here.” But that’s precisely the problem of America. All of those words — “you” and “me” and “here” — are canyons and oceans full of unending sound. What sounds are we remixing and building songs out of? And the instruments we’re using, where did they come from? And who built them?

You can always, always tell when someone is faking a phone call. They’re holding the receiver to their ears and saying every perfect half to a made-up conversation, but there’s something missing. I read a lot of writing like that. It’s not speaking to anyone but themselves. It’s lying and lying about lying.

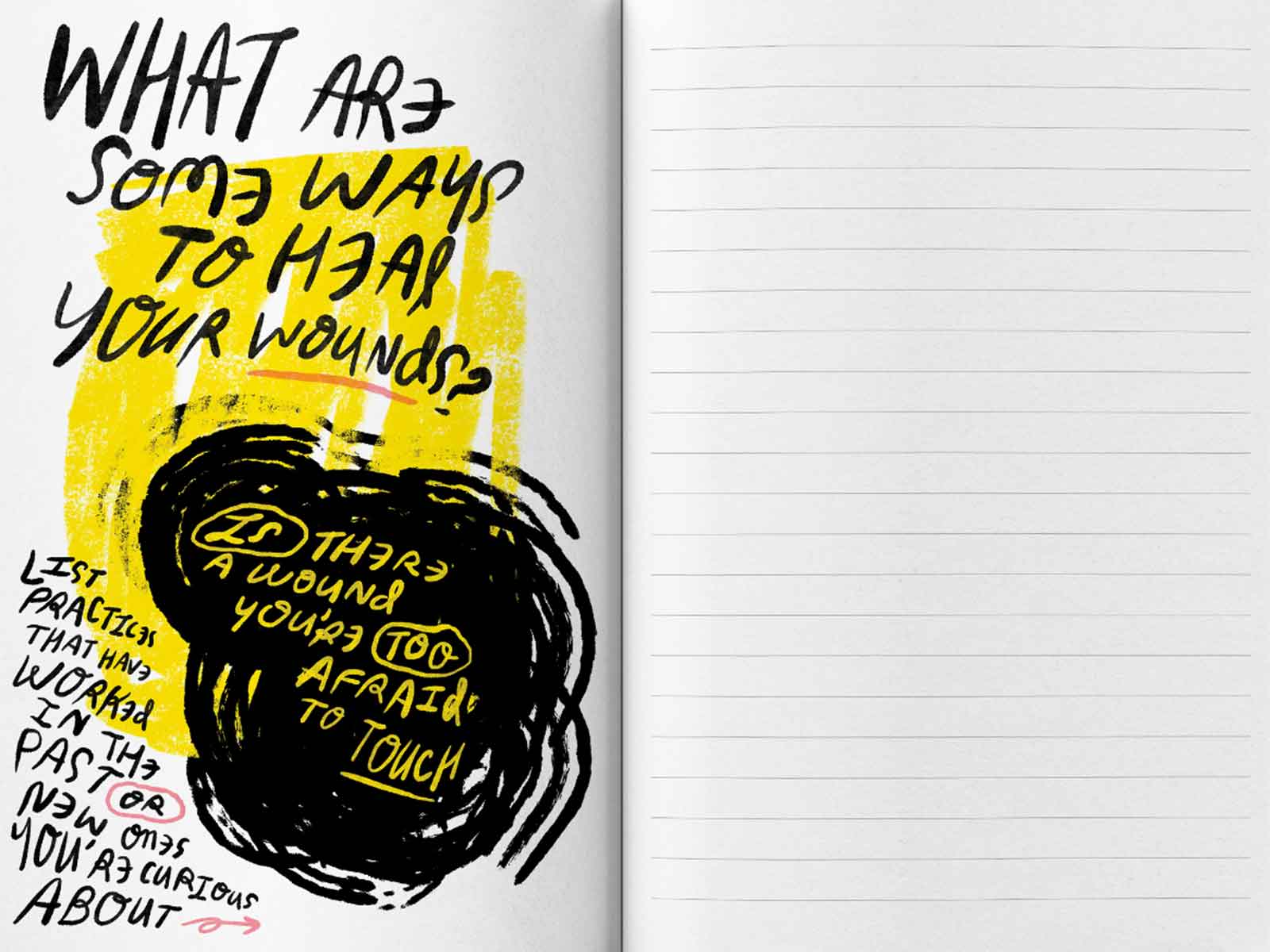

I’ve spent so much time concerned with whether my work is good, entertaining, beautiful, and not enough time figuring out what makes my work necessary, urgent, impactful. I’ve found that I cannot answer these questions without answering to a community, to my dead, and to my family.

Hamilton is speaking to our comfort with a system that we’ve inherited and built upon. And saying it’s worth it, all of it was worth it. The three instances in the musical where it tries to paint his made-up stance against slavery are despicable. But are they really any more horrifying than our history and our capitulation with the racist highways we speed down upon? I don’t know. I’m surviving like you are. I’m going to vote. But I like to think that I’m not painting these things, or my life, my history, and even my imagination, as anything but what it is.

I think, probably unhealthily, of all the avenues and turns my story could have taken.

My dad’s heart lasting another ten, fifteen years. Would he have been one of the 32% of Latino men voting for Trump? Defining Americanness by being anti-Black and anti-immigrant, even if the price of the ticket is fascism? But more than that, I think about if I had stayed in that first elementary school. By high school, some of the classmates I played with were grown-up, and this might be a broad brush, but so many of them just didn’t give a shit about what white people thought. Back then, I was like, they’re whack, they’re rebellious, they’re poor. When actually, they had so much right about the world — how they viewed it, how they lived in it. Their lives, and their likes and dislikes, the way they live, even through the brutality of what capitalism serves up to anyone poor and not born into a white body.

Compare that to how I, and plenty of other people of color, were living (and dreaming and writing), to how much we conformed and responded to whiteness. I tell myself I had to turn my back on my community, but that wasn’t true. It was the wrong fucking choice. Maybe I’ve made some of it up in my twenties. Maybe I’m still wrapped up in a bunch of lies, still mythologizing my choices, still succeeding in a failing system.

Nowadays I cling to the failings in my work more than the successes. There might be honesty there that I missed while my writing was being entertaining and artistically sound.

I don’t think any one person is big enough to damn the whole history of a place, an entire age. But we can live our lives in dissent. We can speak words of genuine, hard-won hope. We can guard our images. We can save the things worth saving, which is mostly ourselves, and believe in things worth believing, which might not be America.