To forget one’s ancestors is to be a brook without a source, a tree without a root.

Chinese Proverb

Confession: I don’t know my ancestors’ names. Also: my Mandarin is lousy. I have never been to our ancestral village. My grandparents were dead before I was a teenager, and I still haven’t set up a proper altar in our house with photographs and incense. I never enrolled my children in Chinese school like I attended every Saturday for ten years. I am destined, it seems, to be a barren brook, a rootless tree: in other words, a bad descendant.

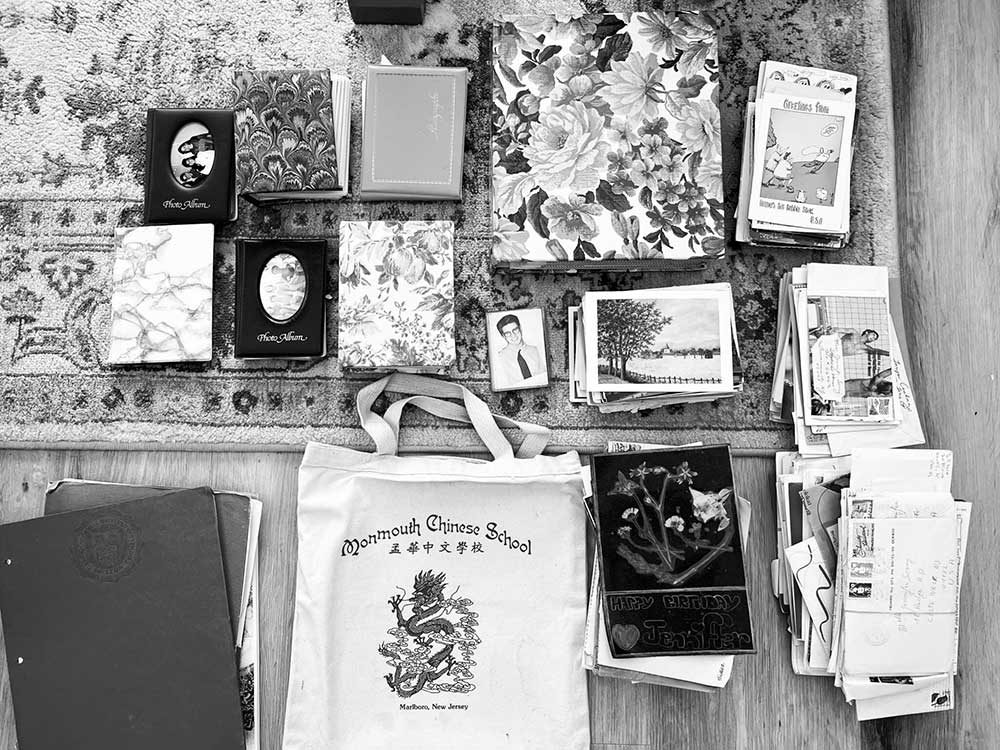

It is almost spring, and our backyard ornamental plum trees in California have already bloomed and dropped their pale pink petals like a wedding procession. Outside, the bright sun is unrelenting, but inside, I am sitting in my office, lost in a swirling fog of thoughts, an archive of photos, letters and memorabilia. I desperately wish I could trace a map with my index finger and draw a line to show my family’s migratory path from mainland China to Taiwan to California. I am also thinking: How do we get to know our ancestors when the bridges of language and shared history are missing? How can we work to understand the trauma that has been passed on when it goes unspoken, and how do we break those silences and cycles of dysfunction?

Intergenerational trauma can cut you off from your roots, fragment your memories and rupture your central nervous system.

To know where you come from is key to belonging.

Intergenerational trauma (also called historical trauma, multigenerational trauma, secondary traumatization) is defined by the American Psychological Association as: “a phenomenon in which descendants of a person who has experienced a terrifying event show adverse emotional and behavioral reactions to the event that are similar to those of the person himself or herself.” Though this has become part of our cultural lingo in recent years, it was not a phrase I had ever heard growing up in New Jersey or studying as a psychology major in college.

I was born in the Year of the Rabbit, an only child of Chinese immigrants who met in New York City. Mandarin was my first language at home. My mother told me that the first time I was dropped off at preschool I waited by the window all day, as if abandoned in a foreign land. Once I set foot in an elementary classroom, I began to lose my mother tongue.

At home, I was ever the Good Daughter, pouring over multiplication flash cards, practicing piano, going to Saturday Chinese school, playing my part in the model minority myth. But there was a cost, too: pressure. I constantly followed the rules, spoken and unspoken, and tried to negotiate a tenuous peace between my bickering parents. I wore Coke-bottle thick glasses and was terrified of the dark. My anxiety churned in my belly and eczema ate away at my arms, elbows and legs.

Once, I was awarded a gold trophy at Chinese school for a speech competition. Confession: my mother wrote the speech. I still have the shiny statuette in my closet. I memorized the speech. While I didn’t understand most of it, I still got laughter at all the right places. I felt like a fraud, but my parents were proud, clapping and beaming in the front row. Inside, I shrunk. It is only in hindsight that I can see how the more I “succeeded” in playing a role, the more I lost my true self. A game I could never win.

Let me tell you a story that first came to me in my dreams:

The girl was lying on the ground, caked earth below and a cloudless sky above. A scarlet blindfold hid her eyes. Her hands and feet, bound with twine. Struggling to get her bearings, she wiggled her bare toes and inhaled the sweet scent of a nearby apricot orchard. Her horizontal body lay only a half-meter away from the edge at the Silver Lake of Forgetting. The constant shushing sound of the ripples steadied her heart.

Suddenly, there was a loud flapping noise near her head. A mighty gust of wind shook the earth and a celestial winged creature, wider than a river barge, landed next to her, casting a long shadow over her torso with a train of sapphire and goldenrod feathers. The girl lay as motionless as a slumbering python. The creature’s hot, soured breath sent a honeycomb chain of hives down her breastbone.

You are far from home, girl. The deep, powerful voice spoke in her head, followed by throaty, wild laughter. She recoiled, the spoils of vinegary bile rising in her throat. She had never heard this ancient guttural language before, yet somehow needed no translation.

Who are you? she asked.

That is for you to answer. You see, this is my kingdom. Well, you can’t see hawhawhaw, until you solve the first riddle:

I am older than the oldest creature you shall ever meet. You can see me in the sky and in the water but when you close your eyes you will think I am a dream. The more you can see me, the more you can remember, the closer you are to dying. My name is an eternal mystery, zephyr whispers morphing from tongue to tongue, hushhushhush.

On the one-year anniversary of the shooting in Atlanta that killed eight people, six of them Asian women, I stood on the Capitol steps in Sacramento with my husband and children. I carried a sign my daughter had drawn that read, “Stop Asian Hate.”

Over the past two years, I have watched the news in horror as Asians have been violently attacked while walking on the street in daylight hours. An Asian elder was punched 125 times in an attack in Yonkers, New York. GuiYang Ma was sweeping a sidewalk when she was attacked in Queens, New York, and died from her injuries. On a Sunday in February this year, a man assaulted seven Asian women in the span of two hours. Christina Yuna Lee was stabbed to death in her apartment after a man followed her home. Michelle Alyssa Go was pushed to her death at a subway station. One report said Asian Americans were more stressed by anti-Asian racism than the pandemic.

Together at the vigil, we chanted, “Our voices matter.” I looked around, comforted by the words of activists and allies, and also fretted that far too few actually care about helping Asians feel safe in our communities. Every time I read a new report, it inevitably triggers old wounds. You do not belong here. Go back to your country. Foreigner.

APA definition continued: “Reactions vary by generation but often include shame, increased anxiety and guilt, a heightened sense of vulnerability and helplessness, low self-esteem, depression, suicidality, substance abuse, dissociation, hypervigilance, intrusive thoughts, difficulty with relationship and attachment to others, difficulty in regulating aggression, and extreme reactivity to stress.”

I could easily put a check mark next to each of these symptoms today, but I once mistook these to be “normal” reactions to growing up in an immigrant household. I had learned how to hide my imperfections. Shiny on the outside, shriveled on the inside. I was completely out of touch with my emotions. I now consider this to be high-functioning anxiety. Sadness or shame was not in my vocabulary, nor was asking for help.

Confession: twenty-five years ago, during my senior year of college, I fell into a suicidal depression and had to take a leave of absence. I say fell, but what I mean is, succumbed, collapsed, disintegrated. I was a shadow haunting my parents’ home.

You open your eyes. You know it’s morning because there is sunlight snaking into your bedroom, sliding past white aluminum blinds in diagonal lines. You have no idea what day it is. It doesn’t matter. The digital clock reads 7:30 in red. You are curled in a fetal position. Your bony fingers are cold. Your toes are lead. You hear footsteps below. You roll over. You point your toes toward the wood floor and coax them to move. You put on clothes your mom has folded and laid on the dresser. You brush your teeth, then your hair. You don’t recognize the girl in the reflection. Cloudy, sunken eyes. Purple circles darken her skin underneath. Her lips are pale, colorless. You are a ghost.

You go downstairs and your parents greet you in the kitchen with false cheer. You wish the shutters were closed. It is too bright. You want to return to bed. You open your mouth but no sound comes out. You have nothing to say. You do not meet their eyes. You don’t want to see their disappointment. You are a forgotten promise.

My parents have never spoken to me about that period of my life. An erasure. For nearly two decades, I never spoke about it either. I believed it was a shameful part of my past, something that was a black mark against my family’s history.

If I never acknowledge the truth, will it disappear, or will it continue to haunt me?

In 2015, Dr. Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry and neuroscience, studied the children of Holocaust survivors and found changes to a gene linked to cortisol levels, a hormone involved in our stress responses. Her epigenetic study suggests trauma experienced by our ancestors could be passed along in our cells. Hearing about her research changed the way I thought about my own trauma. Even if it’s not spoken about or named, it can be felt in my body.

The girl felt the vibrating, pulsing earth beneath her skin and listened for the west wind. A soft whistle, faraway birdsong. A mothwing’s fluttering dispatched goosebumps down her arm. A trio of silver carp leapt in and out of the phosphorescent water nearby, graceful as moonlit ballerinas. She remembered her Popo once murmured a bedtime story about a formidable creature who lived on a lake covered in lotus flowers: part-bird, part-fish, all-knowing.

Her Popo’s voice filled her head, gentle cooing as dreams stirred to life. She wished she could rub the smooth surface of the jade pendant necklace her grandmother gave her when she turned sixteen but her hands were tied. She tilted her head toward familiar whispers and a name came flooding back to her like an old friend resurfacing from the depths of memory.

Peng. You… are… Peng!

A lucky guess, the creature hissed. Flash! Sunlight flooded her face the moment the blindfold vanished. She blinked in her surroundings, hypnotized by Peng outstretched before her, his eyes narrowing with contempt. The winged beast was even more glorious and ghastly than she had imagined, each gold and sapphire feather emblazoned with the song of an archaic land. The lake behind Peng mirrored his reflection; slate gray, lethargic clouds cast a shadow over them.

Growing up, my dad had told me all the photos, letters and books from his family had been lost or burned during war times. I learned to stop asking for details. During his childhood, his town of Chongqing was bombed by Japanese air raids and then in 1949 he and his family fled mainland China to Taiwan during the Communist Revolution.

Four years ago, during a visit to my parents’ home in New Jersey, he handed me a stack of hardbound cardinal red books: our jiā pǔ, or genealogy records (jiā 家is the Chinese word for “home” and “family”). Many jiā pǔ were written on the walls of family village temples and destroyed in 1949. These volumes were filled with hundreds and hundreds of names dating back to 5 B.C.E. tracing our ancestral lineage and migration patterns. My dad had forgotten they existed; they had been sitting in his garage. In the 1980s, his father had organized a collection of these books. There is an inscription inside one from him to my father.

At the time, this discovery felt like a revelation. Now they sit on a lower shelf in my bedroom, gathering dust. Confession: I don’t thumb through them very often. I can’t remember what page contains my name.

The next riddle will be harder, girl. You may know my name, but you do not yet know my power. Tell me, what is the one thing that destroys all creatures, forests and deserts, is stronger than iron and steel, ousts emperors and razes whole civilizations?

As Peng lifted his mammoth wings, a deafening wail-shrieking rose on the wind. On the ground, the girl writhed, desperate to shield her ears but her arms were still bound. She felt like she was forced to endure the grief of an entire species. After what felt like hours, the shrieking subsided; her eardrums reverberated with pain. She remembered when she was little, her Popo would rub a peppermint balm on her skin after a scrape and comfort her with a kiss. Give it time, she said. Even though her Popo was long gone, she could hear her honeyed voice clear in her head. She blinked, her lips turned up with confidence.

I will answer your riddle, Peng, and you will untie me.

You are stalling. You will be stuck here with me for eternity.

She held the creature’s gaze for what felt like a lifetime. She looked at the lake’s edge and noticed what she originally thought were pearlescent shells and stones were actually chips of bones that had been washed ashore for centuries. What a lonely life. She shivered, a gust of wind carrying an echo from afar.

Time. That is my answer. Now free my hands.

Peng coughed in disbelief. Luck again. He pointed a wing towards her back, untying the twine. She sat upright and stretched, blood flow returning to her limbs.

The past two years have brought wave upon wave of uncertainties. When my kids’ schools shut down, I marked the calendar as day 1. I couldn’t imagine it would last more than three months. How naïve. When I got to day 100, I stopped counting. Although I have spent most of my life catastrophizing, I never imagined a global pandemic would upend daily life and rob more than six million people of their lives.

Around the Lunar New Year of the water tiger, I started to collage, foraging through a basket of magazines, cards and scraps. I am drawn to Asian faces, looking for someone to mirror my own experiences. Something about using my hands to tear bits of paper, cut angular shapes, tape down images and arrange ripped pieces into something whole is reassuring, meditative. There is no prescribed product, only found beauty. Collaging is my balm.

One last riddle before you can leave: What can bring back the dead, make you cry, make you laugh, make you young, born in an instant yet lasts a lifetime?

The girl closed her eyes and rubbed her jade pendant, immediately thinking of her grandmother and her floral perfume. Near the end of her life, Popo forgot how to cook her favorite rice soup but she never forgot to kiss her granddaughter’s forehead at bedtime. Remember, I love you, she said, smelling of jasmine and honeysuckle. Tears dampened her cheeks; she missed Popo every day. That’s it. She opened her eyes.

I know the answer, she said. Memory. Memory is what brings back the dead and lasts a lifetime.

Clever girl, Peng said. Here is the key. You can leave here but you will take nothing with you. This is the Silver Lake of Forgetting. You will go back to your world of convenience stores, heaps of garbage, screens of oblivion, where you will forget what is most important. You will forget what it means to be free.

*

For years, I stored my maternal grandmother’s black silk fur-lined coat in the back of my closet. It was one of the few possessions I had of hers; my aunt mailed it to me after her divorce. During a spring cleaning, I took the coat out of the dusty closet, gently pinching the shoulders to remove a dry cleaner’s sleeve that clung to its smooth contours. Slowly, I undid the knotted buttons down the middle and opened the front. Suddenly, there was a fluttering, waves of translucent wings in motion. Gasping in surprise, I quickly closed it and swooped it down the stairs and out to the back deck. There, I laid it on the ground. When I dared to open it again, hundreds and hundreds of moths flew out, a sea of glassy wings bound for the clouds. An exodus!

After the shock passed, I carefully placed the tainted coat into a trash bag and later disposed of it with the garbage. I had so little passed from my ancestors; my Popo’s exquisite coat was another loss, an empty space devoid of inherited treasures. Recently, I went searching for a photograph of this coat but came up empty-handed. I don’t even know if my memory of this coat matches reality.

The girl traced the outline of the brass skeleton key with a circular ring handle and three mazelike teeth. A rush of pride swelled to her head. She had solved the three riddles. She was no longer a captive. Then she looked up and stared into Peng’s eyes, sensing something familiar deep within. What was hiding back there? She saw gray clouds churning in his eyes. A chill prickled her neck. It was a feeling she knew: loneliness. His words rang in her ears. You will be stuck here for eternity. Ahh so, he was the one who was trapped—not her.

I don’t need the key, she said. I am already free. Here, you take it.

Peng stared at the key and back at her, surprise filling his eyes.

You. He was seeing her for the first time. You… are the one I have been waiting for. Thank you.

Peng bowed his head. He turned toward the glowing sun, stretching his sapphire and gold wings to their full glory. A steady beat thrummed as he took off, wings beating like tanggu drummers. The blazing rays warmed her limbs as color returned to her persimmon cheeks. She felt lighter watching Peng soar higher and higher until his whipping tail dissolved into soft, milky clouds.

The night after the vigil in Sacramento, I watched Pixar’s Turning Red with my children. I laughed and cried watching a young girl trying to be perfect for her family and getting crushed by the weight of filial duty. I felt a surge of warmth in my chest seeing this story playing out on screen. I hope to one day share stories like this, of struggle and strength, with my children.

For what is the opposite of trauma if not love.

When I threw away my grandmother’s moth-ravaged coat, I believed I had broken another bond, albeit tenuous, between me and my ancestors. What I see now is that my inheritance is not immutable. I have the power to write the story I need most.

Perhaps you need it too.

These are the kind of stories I wish I had heard growing up and carry wisps of truth from dreams and lullabies. They are stories where I see myself and more importantly, I have agency in the choices that are made. I am the heroine of my stories, something I never saw in books or movies as a child. It is far easier to write about a girl solving a mythical creature’s riddles than to wax poetic about intergenerational trauma.

Confession: mine is not a sorrowful tale. It is a story of rebirth, an awakening, a reckoning. My ancestors are guiding my open palms toward a future—one gilded with hope and wool-lined with resilience.

I can hear their voices: Do not sleepwalk through this life. Do not join lockstep with the gatekeepers, the colonizers, the white supremacists. Breathe and awaken, Daughter, listen to the unstoppable drumbeat, your continuous heartbeat. This is your time to imagine radical joy and celebrate being alive. We are with you. We bear witness.

What do I hold sacred now? Many truths. Just like the girl at the Silver Lake of Forgetting set herself free, I can choose freedom from shame and secrecy. I must speak up to fill the silences, working to combat the erasure of my past and fight anti-Asian violence in our communities. The pain I endured as a child is no longer dismissed. Joy and sorrow, hand in hand, can accompany me and my family. I have set up a table altar displaying our jiā pǔ and plan to add photographs of my ancestors. I don’t have a map or guide for how to break the cycles of dysfunction, but what I do know deep in my bones is this: healing is possible, and that is the jeweled inheritance I hope to pass down to my children and future generations to come. You hold the key now.

The collage art throughout this piece was created by Jen Soong to accompany the text.