“Life’s what you see in people’s eyes; life’s what they learn, and, having learnt it, never, though they seek to hide it, cease to be aware of.”

— Virginia Woolf 1

At age four, I used to secretly squeeze through the cracks in our backyard fence to go and explore the world on the other side. One step at a time, a little further each time, those childhood escapades soon grew into what would become the quest of a lifetime: a relentless and passionate chase for “what lies beyond.” Beyond the backyard fence, beyond sight, beyond the human scope — a chase, one might say, for the true essence of the world. So I wandered and wondered, from one country to the next and from mathematics to glass — to art.

I have, of course, never touched the essence of the world — it is not ours to reach. Yet gazing at the horizon one can still gather a sense of infinity. Aware though I may be of my corporeal limitations, mind anchored to body and feet anchored to the ground, I have long questioned the confines of the human experience, the hazy frontier between our sensory capabilities and the real world beyond. That is not unexplored ground: Plato already, in his Phaedo, hints at a similar inquiry. “Then when does the soul attain to truth? For when it tries to consider anything in company with the body, it is evidently deceived by it.”2

What is more, the word body in Plato’s writings does not simply denote the physical body; rather, it alludes to a whole integrative perspective. It is the habitual, passive, unquestioning standpoint of everyday life — it is non-being, where everything is “embedded in a kind of nondescript cotton wool.”3 Soul, in turn, refers to the viewpoint of the aware mind, that which is in a state of being, stretching out from the body toward truth. Toward, but never to. For the soul stands in limbo between body and truth, its ties with the former keeping the latter out of reach, much in the same way that being is a personal experience of the truth and not the truth itself. Truth as such lies altogether beyond the human scope, in a place sheltered from interference and commotion and noise — a place bathed in silence. And indeed every time I have experienced being, it has been accompanied by a profound, extraordinary silence, as if the din of everyday life had been altogether stilled.

Could it be, I sometimes wonder, that silence is the expression of the essence of the world?

Certainly I have encountered several different forms of silence — and perhaps even more different forms of noise — over the course of my life; some more specific to childhood, others to nature, others still to art, to Japan, to love, to loss, to loneliness. But nothing, to this day, has bestowed greater silence upon me than mathematics. (Here I must insist: mathematics, not arithmetic. The two are often mistaken for one another. Yet they differ in the same way that grammar differs from literature.) Mathematics are immaterial by nature, intangible, impassive; they are a construct of the mind, supported by the physical world yet disconnected from it. They are made for the most part of sharp lines and clear-cut answers, black and white, true or false. A form of perfection, a haven for the soul, removed from the perpetual chaos and uncertainty of our worldly reality.

Tremendous poetry resounds within the seemingly austere silence of mathematics — a poetry soothing and bright which (as poetry does) bypasses reason to reach out directly to the soul, making emotions vibrate like sympathetic strings. The kind of poetry, one might say, that makes mathematicians resolve to become artists.

For artists and viewers alike, the experience of art is a most peculiar one: outwardly purposeless, unpredictable, serendipitous and deeply personal all at the same time. Its power lies in its very complexity, so reminiscent of human nature, so evocative of ourselves, so propitious to self-reflection. “But when the self speaks to the self, who is speaking?”4 That is, perhaps, the question which art most persistently asks: Who is speaking? All of my selves, it seems, are speaking at the same time. My four-year-old self by the backyard fence; my nineteen-year-old self taking a math exam; my twenty-eight-year-old self in Japan; and all my other selves too, the one who was raised in the snows of Canada, the one who travels compulsively, the one who blows glass, the little girl, the grown-up woman — all those selves that have experienced being and shaped my vision of the world. Their voices echo with mine; yet they are not mine. My true voice is of a different nature: my true voice belongs to life itself .5 But who is speaking?

As I delve deeper and deeper into the intimacy of my art-making, trying, in vain — for it can only be in vain — to answer that question, I patiently sift through the voices of my different selves as one would pan sand for gold: seeking the minuscule pearls of silence that I share with the essence of the world.

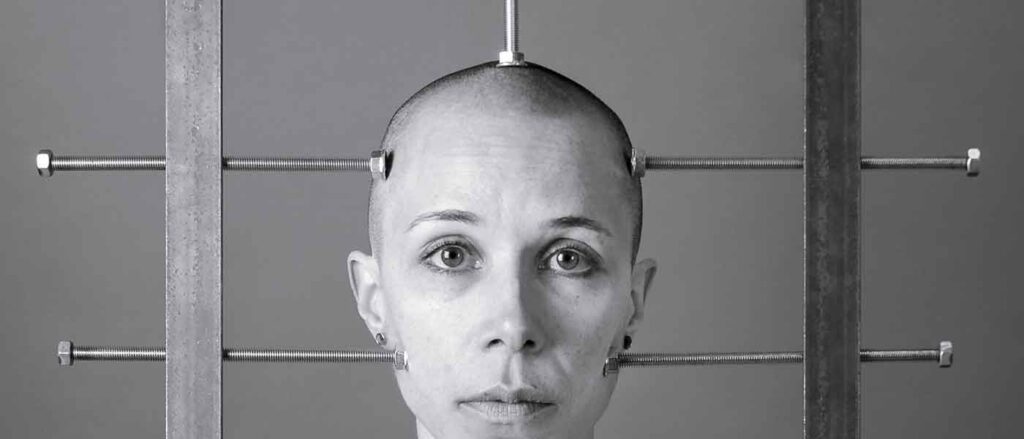

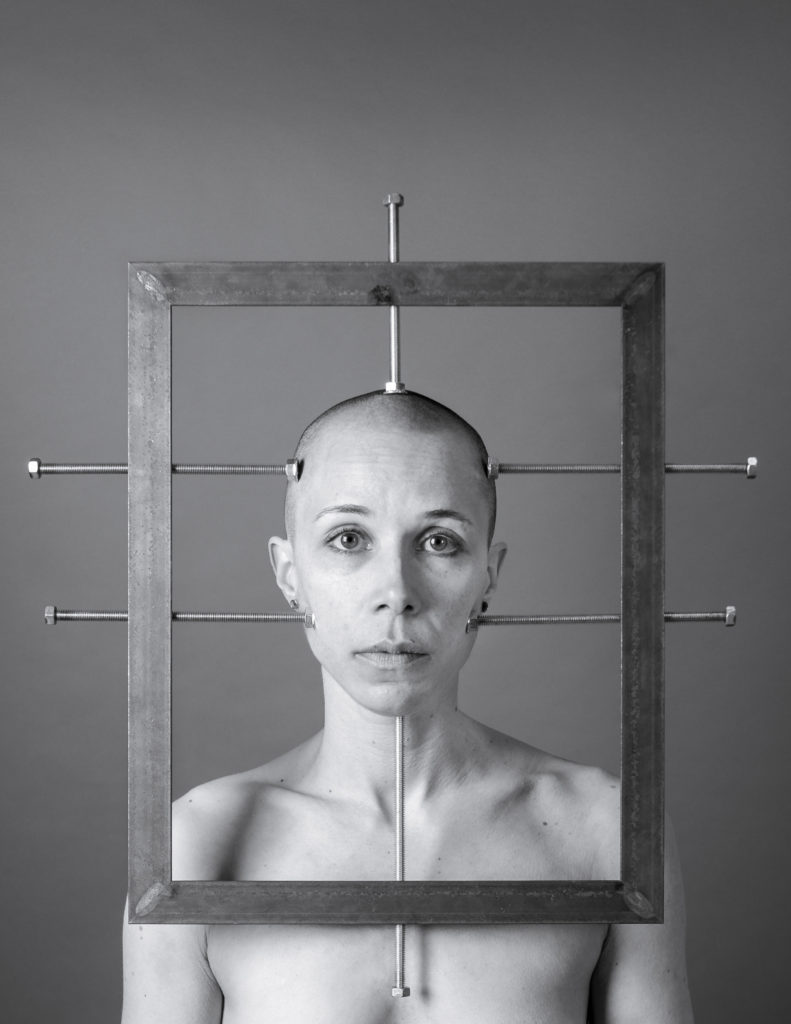

This is an original excerpt from Amélie Girard’s full academic thesis, “Beyond the Noise, Behind the Cotton Wool: Reflections on truth, silence, and the outward purposelessness of art.” The selection of text was specifically chosen to address the theme of this issue, Artificial Realities, with the express purpose of accompanying the featured image, Mise En Abyme, a still-life portrait taken by Amélie. You can read her full thesis here.

- An Unwritten Novel. In: Woolf, 1920/1989, p.112.

- Phaedo. In: Plato, trans. 1953, p.227.

- A Sketch of the Past. In: Woolf, 1939/1985, p.70.

4 An Unwritten Novel. In: Woolf, 1920/1989, p.120. - Character in Fiction. In: Woolf, 1924/1994, p.436.

References:

Plato. (1953). Plato I: Euthyphro, Apology, Crito, Phaedo, Phaedrus (H.N. Fowler, Trans.). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. (Original work written ca. 360 B.C.)

Woolf, V. (1994). The Essays of Virginia Woolf, Volume 3: 1919 to 1924. A. McNeillie (Ed.). Orlando, FL: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. (Original works published 1919-1924)

Woolf, V. (1989). The Complete Shorter Fiction of Virginia Woolf (2nd ed.). Orlando, FL: Harcourt. (Original works published 1917-1941)

Woolf, V. (1985). Moments of Being (2nd ed.). San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace and Company. (Original work written 1939)