My sense of what it means to be an American woman, a queer Aries snowflake, shifts every time I leave and return to my own country. As a teenager, optimism propelled my feet to wander European cities after dark, scoff at consumer tourism, and relish risks. From Venice to Mumbai, I stayed in far-off places long enough for a mash of local mannerisms to leave a residue on my being, mannerisms such as a temporary Scottish lilt and a Southern Indian’s head wobble. Only when I had a basis of comparison did I get a sense of my identity via nationality, sex, and skin. Privilege belongs to those unaware, and I wasn’t aware of my American-ness and assumed passport privilege until I left the rural boundaries of my Pennsylvanian hometown, until I stood in the dock of a locked Indian courtroom and defended the validity of my own testimony against the projection of foreign “otherness.”

Being an “other” in India gave me a tiny glimpse of what it might mean to be an “other” in my own country. This was painfully apparent after I flew home at the end of 2016’s vitriolic election year. I arrived in time to be surprised by Trump’s successful campaign tactics. As the clock approached midnight and the tally of electoral votes continued to rise, my friends and I accused all Republicans of voting for cultural preservation of hegemonic white America, for perpetuating the psychological damage that results from racism and violence.

Later, when I could partially put my own biases to the side, people I loved admitted to feeling trapped between two repulsive candidates. Some on the Right also seemed to want to establish a kind of “American identity” for themselves that prioritizes law over compassion or integrity. The reasons for the success of Trump’s campaign are complicated, and my interpretations of friends and family only represent part of the answer.

I’m still grappling with questions raised in the minds of so many Americans. Both political parties seem unable to grant space for the testimony of others with different points of view. What are we willing to overlook (sexual assault, murder, money laundering) to establish a sense of political, cultural, and spiritual security? How do we accommodate, even accept, these varying perspectives without marginalizing one another? Is it possible to extend dignity for both the winners and losers of the election? Some days I’m not sure I want to.

In 2015, I lived abroad in the green sliver of Kerala, India, for a year as an ESL teacher; this was my second time visiting the lush state. When I stepped out of the airport into the equatorial humidity, I felt an immediate spirit shift. In my other homes, time moved at a clip, and the space between people was guarded. Coming from northern Pennsylvania, I was used to rugged space from one tree to the next, space between floors and high ceilings of drafty Victorian houses, and emotional and physical space between strangers. But India must be more economical.

During my first few weeks in the country, navigating from one part of town to another was an intimidating task. The town centre was mouldy bread buildings stained with rain and an onslaught of advertisements. No Helvetica. My illiterate eyes couldn’t follow the typographical curls of Malayalam. Narrow closet-sized stores selling cigarettes and spicy banana chips looked like precarious stacks of billboards slapped together with concrete. Abandoned flip-flops and trash, like blue and orange confetti, decorated the edges of roads and gutters.

But we teachers lived outside of town, relegated to a marginal space, a dilapidated hotel a few minutes from the train station and situated in the middle of a cow pasture. The crumbling hotel was filled with solitary people passing through, grizzled pilots from Delhi and isolated escort girls from the Ukraine. My new home was a space marked out for foreigners and transients. Despite having grown up on the edges of Appalachia, this rural quietude was as surprising as the cramped city centre.

I had a room of my own, a fan, a firm mattress, and a tiny balcony for hanging clothes. Introversion was uncommon, and we teachers spent most of our time together. At night, neighbours invited me to the roof for brandy and cigars, and in the mornings, a neighbour tried to court me by bringing sweet coffee in a china cup. I was seldom alone, even in my own bedroom.

Adapting to different living conditions wasn’t a new experience. In my early twenties I had roamed the country as a tourist, and Indian college friends have extended an invitation to immigrate to their country ever since. On my first visit, all of India seemed intoxicating and unexpected. The more unsavoury my travel experiences, the more authentic they felt.

After a seven year gap of living in misty, monochromatic places, I longed for humidity and a sun hot enough to burn skin through fabric. I missed the tactile senses of eating curry with my right hand and feeling marble floors under my bare feet. Drifting vagabond life also allowed me to remake myself, and along with this freedom came the sense of unaccountable anonymity. I saw myself as an observant cultural voyeur, but didn’t consider how travel would remake me in non-consensual, unavoidable ways.

On my second trip to the country, I floundered into a classroom with wide-eyed, beautifully dressed students ranging in age from 15 to 65. Three days after I started teaching I realized they couldn’t understand a word of my American accent. My students stood up when I entered a room and called me, “Karn ma’am.”

During lunch breaks, students found me sleeping on the roof of the school. I lounged with my eyes closed against the sun while they practiced conversations about food, love, and politics in the present tense. The girls took my hands, snaked slender arms around mine, and shared gossip. People knew every external titbit about me — where I went to dinner, which boys walked me home, and how I had been spotted with one of the other teachers, “under an umbrella!”

Students would say, “Madam! Why did you cut your hair? You look like Harry Potter.”

“Madam! You have too many boyfriends. Such a devil!”

We entertained one another with small scandals.

“Can you hack it here?” a thirty-something teacher asked. “No one is safe from policing.”

I didn’t feel policed, simply the subject of invasive curiosity and moral judgment. The stereotypes associated with my nationality dictated various first impressions: I was often asked to account for the actions of my government, Hollywood presented a version of American women I had neither the time nor the energy to live up to, and words I might have used to describe parts of my identity, like “pansexual feminist,” had negative connotations in my host community.

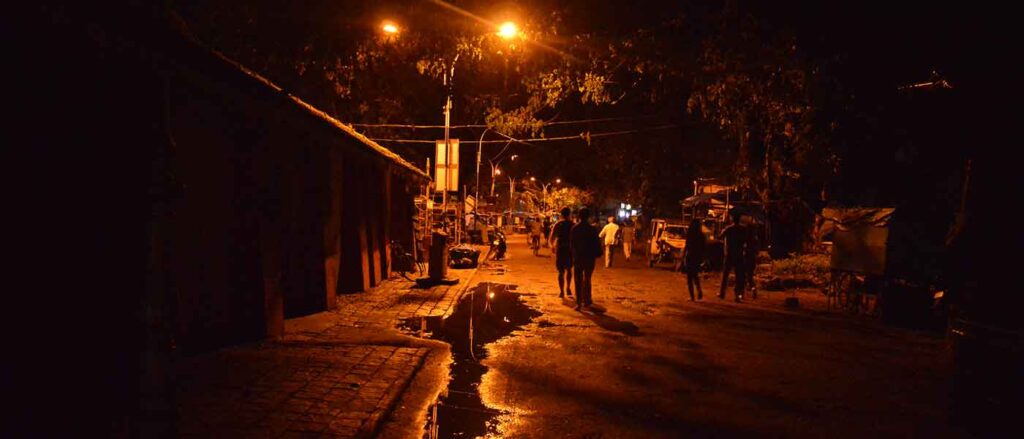

After living in India for almost a year, I was so at ease that I often took walks in the cool evenings to enjoy lights that were strung across courtyards and music that played from balconies. Parts of me felt at home. We expat teachers, many of whom were from western countries, respected what cultural rules we were aware of. While some locals regarded us as debauched tarts, others made space for us. We spent most of our free time eating and learning to cook beautiful curries. We belched, wiped heat from our eyelids, and asked each other, “More rice with your rice?”

My Indian friends would cry, “Chetan! Devil! You’re getting fat. This is a good thing. India is taking care of you. You were too thin before.” I ate until I grew out of all my trousers and ditched western clothes. We assimilated to traditional expectations of modesty and wore leggings under handmade kurtas. All of us expats were in various stages of being remade by the pace of daily life, the culture, the climate, and the people we connected with and rallied against.

We relaxed into fluid, unhurried time. Simple decisions took hours, sometimes weeks. Where my friends and coworkers ate dinner was agreed upon when all the people we knew had been invited and after preferences for alcohol/northern Indian politics/red meat had been taken into account. What’s mine is yours and what’s yours will be given to complete strangers whenever the need arises. No one ever seemed to know what was going on, where we were, what time it was. The exotic or shocking became mundane. We shrugged when the electricity failed in the elevator or when a workers’ strike kept us indoors for a day.

Before I left for India the second time, male friends asked about the frequency of Eve teasing, or sexual harassment, on the streets. I dismissed their concerns and took their awareness of risk as a racist assumption that one country had a monopoly on gender-based violence. The risk of being groped by a stranger in a public place is common for women everywhere, even in the shire of my conservative hometown.

My savvy students wanted me to be well-fed, aware of my surroundings, and safe. Towards the ends of one-on-one speaking sessions with some of my students, girls with beautiful names would sometimes tell me which recipe I should cook that night and, in the same breath, how to be careful while traveling.

They would say, “You must see the waterfalls and the tea fields in Munnar. This is the most beautiful state in India. But take a safety pin for the crowded buses because you never know who might be touching you.”

One night, following a dinner with friends, I ignored an internal check and walked home from the gathering alone. I walked the length of half a block, out of earshot, and down a quiet residential street towards my apartment. In the tick of ten minutes, a stranger pitched towards me, heaved onto me, and started a ripple effect of loss.

The following morning, I was taken to the police station. I sat in an open room in front of a police officer’s desk while young men loped past to pay parking tickets and others queued along the back wall. Amidst the movement of people, my testimony was edited via a translator who never spoke to me or made eye contact. I turned my face to the slow whir of the ceiling fan as a bead of sweat trickled down my spine.

“A white man?” a local passing through the station asked. “Bengali?”

“No,” I shook my head.

The validity of my testimony was debated and filtered through three people before hitting the carbon paper and passed over to me to sign. I couldn’t verify details in the elegant script or check for content errors. But after several hours at the police station, the teeth marks on my face had attracted ogling rubberneckers milling about the open room. So I signed to escape, and my story was published in the newspaper. For months, I received a trickle of sympathy notes, advice, and the occasional accusation.

In some ways, public reaction was worse than my private experience. It exposed the “us” vs. “them” mentality simmering below the veneer of collegiate respect in the staff break room, in the classroom, and in the streets. I was reminded I was a foreigner out of place. Friends and peers offered well-meaning but frequently misplaced advice.

“If this happens again, take a photo. It will be much easier for the police the next time.”

“We’re not all bad, you know?”

“His life will be ruined. He has suffered enough. Let this drop.”

“You should buy a bike,” said my European employer with a nod. “You’ll be less of a target. They all think westerners want to be raped.” She paused and asked, “Can I make you a cup of tea?”

“But this is bad for the school’s business. We cannot let the students know.”

“White people fears. But if you pay, certainly this can be taken care of.”

“What were you doing out at night? Did you overstep the boundaries of your modesty?”

I lived in India because I loved the hum of organized chaos and colour. Now I was afraid to walk to the corner store for bananas. My Indian friends, coworkers, and supervisors were mortified. “This is one of the safest places in the country,” they said. I reassured them on a repeat loop that my experience had no impact on my love for their culture. Women are targets of sexual violence everywhere. We teachers wanted to return to our routines and to recover as soon as possible from grief. I stayed at the school long enough for my experience to be old news and returned home to the States as the holidays approached.

The police did not speak with me directly, but speculative coworkers declared that the man who assaulted me would be put away for several years. He was released after six months. Lack of physical evidence. No fingerprints on underwear or skin, and a passing witness wasn’t prepared to say what he had interrupted. The case was the word of a careless foreigner against a local boy. I imagined that he was a boy who came from wealth, bearing an old Christian name. But I was never given his name despite his teeth marks in my skin. He is a grunt and a growl in my memory, a flash of teeth and nails. Forgiveness is easier if he stays a damaged animal, a fragment of a nightmare.

Trump’s crude justification for his sense of entitlement to women’s bodies — “boys will be boys” — was painfully familiar to hear upon my return to the States. While some members of his party asked him to step down as a result of alleged sexual assault and his infamous “grab ‘em by the pussy” line, others dismissed this as “locker room talk” and were willing to accept him as a viable leader.

Because of my experience with a sexual predator, Trump’s cavalier attitude towards sexual assault dwarfed my other concerns about his candidacy. While I didn’t need my experience to factor into the decisions of the voting public, I expected more from my loved ones. I was grieved that the Republican party’s rhetoric regarding women and other minorities was so easily overlooked by those closest to me. The election of a man who promotes rape culture undermines my year of learning to say I have a right to mourn my damaged sense of autonomy.

What concerns me is that Trump possesses the same type of entitlement as the young man who crashed into me in India. Privilege and entitlement lead to all sorts of confusion. Am I disposable? Do I have a right to physical boundaries? To a safe space within my own body? If I forget where I am and what belongs to me, I can re-establish my precarious autonomy by mapping boundaries and marking the present tense on my wrists.

While I was abroad in India, the psychological damage of rape culture wasn’t acknowledged, and it sometimes seems to mean little in the States. As a foreigner, my experience was stripped of significance when I was subtly asked to make allowances for a rich young man, and I feel this now in my own country as I and many others are asked to make allowances for a rich old man.

Landing at JFK airport upon my return from India the second time granted the relief of anonymity. I weighed less than I did in high school and had the thigh gap I never wanted. Back behind borders, I returned to the remote hollow where I grew up. I curled myself behind locked doors, and slept in a state of hibernative healing. I recovered from physical and mental scars, from the risks of stepping beyond the emotional and physical boundaries I had been warned about, beyond the boundaries of familiar landscapes, and beyond the boundaries of acceptable behaviour for a young woman. Only after I returned home did I realize which parts of me had been rearranged under that street lamp in India. I spent a year adjusting to re-entry shock, a sliding scale of mental health, and what it meant to be a woman in America. I came out into the sunlight in the spring, burned the underwear I was wearing the night of my attack, and took up kickboxing. I have remained hidden in my hollow, and the man who assaulted me has remained behind the boundaries of a distant country.

Since the election, the boundaries and space between some of my friends and family have shifted. Patriarchal residue is more obvious now. We are separated by jagged space, a space of morality, gender, sexuality, financial success, age, and sibling hierarchy. For those who benefit the most from Trump’s presidency and who are more comfortable with the clear roles defined by a patriarchal culture, the risks of crossing the jagged space are higher. We could get cut should we try to enter it. To question why we create “others” or look away from certain policies involves an unsettling challenge to the status quo. To question what we believe and what we know about ourselves in order to cross boundaries is terrifying.

We can try to cross jagged spaces by establishing common footing, but blood ties aren’t always enough to persuade us to close the distance between us. But if we don’t, we risk dehumanizing people we love, and creating the “other” because of cultural or religious divisions.

The creation of an identity and the telling of testimony is not enough. The capacity to witness someone else’s testimony, even if the speaker and audience have nothing in common, is a powerful gift of humanizing dignity. My sense is that we all want to be heard, valued, and given space for our testimonies. But the act of giving testimony is reciprocal. We need to be heard by those who disagree with us and engaged by those who feel threatened. I want to know that abused women have permission to grieve publicly without fear of accusation or shame. And that all of us who live here, who were brought here, were born here, moved here, belong here. What I hope for is that we’ll be able to give each other a moment of understanding, agency, and, yes, space to find and hear our voices.

What I need from Republican family and friends is to know that my testimony is as valid as theirs, spoken in a language intelligible to all of us. Perhaps you aren’t ready to come into my space, but can I come into yours?