We were born with matching mirrored birthmarks—one above the right kneecap, and the other above the left. Because we were born apart, we did not realize our symmetry until a sleepover, when one of our mothers was busy in the cooking shed, shielding the house from the smells and splatters of burning oil.

We knew each other as well as people whose presence only existed within the bounds of school and self-created battlefields. We braided our hair together in a collective plait, thick enough to strangle the trunks of the small trees that sprouted in the play yard. The yard only offered a twig of protection against the beating sun, which bounced off the black of the asphalt and amplified. When we played Red Rover, no one could break through the knots that tied our heads together. The other kids said we were cheating.

After that, we created a kingdom in the muddy ruins from the failed construction of the neighborhood. When we first arrived, the neighborhood was expanding, with new houses growing out of yards every month. The bones of the planned homes remained, though everyone ran out of money to the point that our mothers and fathers stayed home instead of going to work. The riches of the earth loomed large and shadowed over the rest of the playground and we staked our claim by mixing our spit in the soil. We carved out a throne for the two of us to share, but accidentally smithed it too small, so one of us was always tumbling from the other’s lap as we luxuriated in what we had formed together. We built bunnies out of clay, which we took to be our subjects, and mashed our noses against their sweat, sniffing them in until our nostrils were blocked with dirt. We couldn’t comprehend what ownership was, so we took the territory with the brute force we heard our parents whisper about, the reasons they said we were growing in the humidity of corn and not the humidity of jungle.

We proclaimed ourselves queens of the hill and pushed every invader off of the muck of the mountain. The boys, who spent their time in class pulling at the straps of our shirts, trying to feel if we were wearing bras, would make attempts at deeper dominations by stating the throne we shaped belonged to them. They’d press their butts into our seat, their bodies bigger than ours, deforming our throne with their heft, until it was marked in indents that matched their muscles and fat. When they worked to crush the bodies of the clay bunnies which clung to the sides of the hill, we joined our hands together to create a larger fist and bludgeoned them off the mountain, laughing at their splatters, waiting for crows to rush their bodies.

But the crows stayed clawed to the chain-link fence which told us where we could not be, and the boys shook off the dust of the ground to pull at us another day, until one of them got so frustrated he could not win us over that he threw himself at the pavement behind the dirt mound, within the confines of the cement outline of a house that was never built. He dragged himself against the embedded rocks that marked the room we had imagined would be a kitchen, until he was scraped with blood dripping from his shins, which acted as a glue as he rolled into the dirt. The confetti of the earth and rocks clung to him in a glittering meld of greys and maroons.

This was used as evidence to separate us. While we claimed and claimed it wasn’t us, his mom came to the school to show his broken pale skin as evidence of what they called bullying. This allowed the boys in class to peck at us with an itching hunger, while our bodies were never not being touched. The hair pulling and shoulder grabbing and butt smacking became more overt, but when we went to our teacher about our complaints, she told us that tattling was unattractive and we shouldn’t make up lies about the boys we bullied. They were very good boys, after all, from very good families who would never do anything so undignified.

Our hair began to fall out in clumps, the strands missing one another, aching to be connected. We knew our locks escaped our scalp in hopes they could meet once again in the tangled smells of school garbage. We tried to stare at each other in class, but we were split further and moved so the only parts of ourselves that could be glimpsed was a swaying sliver of profile. The crescent of face held us in class, until we could make our escape and join together for as long as we could in the echoes of the school’s final bell.

We made our way home, carrying each other’s backpacks so we could understand the weight of gravity that held us in place. We would scour the sidewalks for treasure in our linked walk home, trading them as our paths diverged and we were forced to leave one another again. A rock with an exceptionally round hole was exchanged for a four-leaf clover. A string of dandelions for an empty bottle that had not shattered. The teeth-marked plastic green fish for a hard candy, slightly melted from the sun, but still in its wrapper.

We spent our returning walks scheming about the ways we might be allowed over to one another’s homes. Neither of us was allowed to sleep over at anyone else’s houses and neither of us lived in a place that was particularly welcoming of guests. One of our mothers was too proud of the spotless home she spent her life fighting against until she was so worn down by invisible motes, she’d disappear into the cave of her bedroom, watching dramas until she emerged with freshly pressed skin, days later. The other’s mother was too ashamed of the clutter she procured, unable to let go of a plastic bag or a scrap of cardboard until each component of the house was bursting with collections of found objects.

Our mothers were created in an era of lies, which were swapped and traded for the new forms of currency when the old ones stopped working. They knew how to tell an untruth from the tingle of a jaw or a misplaced inhale of breath. This meant there was no considerate excuse we could make up to put ourselves together. Though we were sent home with notes proclaiming our alleged crimes, we shredded the pieces of paper and stuffed them into our mouths until the cursive letters dissolved and disappeared within the acid of our stomachs, our mothers never discovering our meal.

We were able to come up with a plan of half-truths, which meant they were not lies, and told our mothers that we needed to work on our Civics project and had to sort out a way to serve our community. One of our mothers told us that giving our cousins last year’s school books and too-small clothing and video games– which we still played and still wanted but which made too many annoying noises and made our mother burst into screams– should count as service. We told her that we needed to serve more than just our family, which made her suck in her teeth until her eyes sunk in and her cheekbones jutted out. But this strategy worked, and we found ourselves peeling our clothing back to see if our bodies matched.

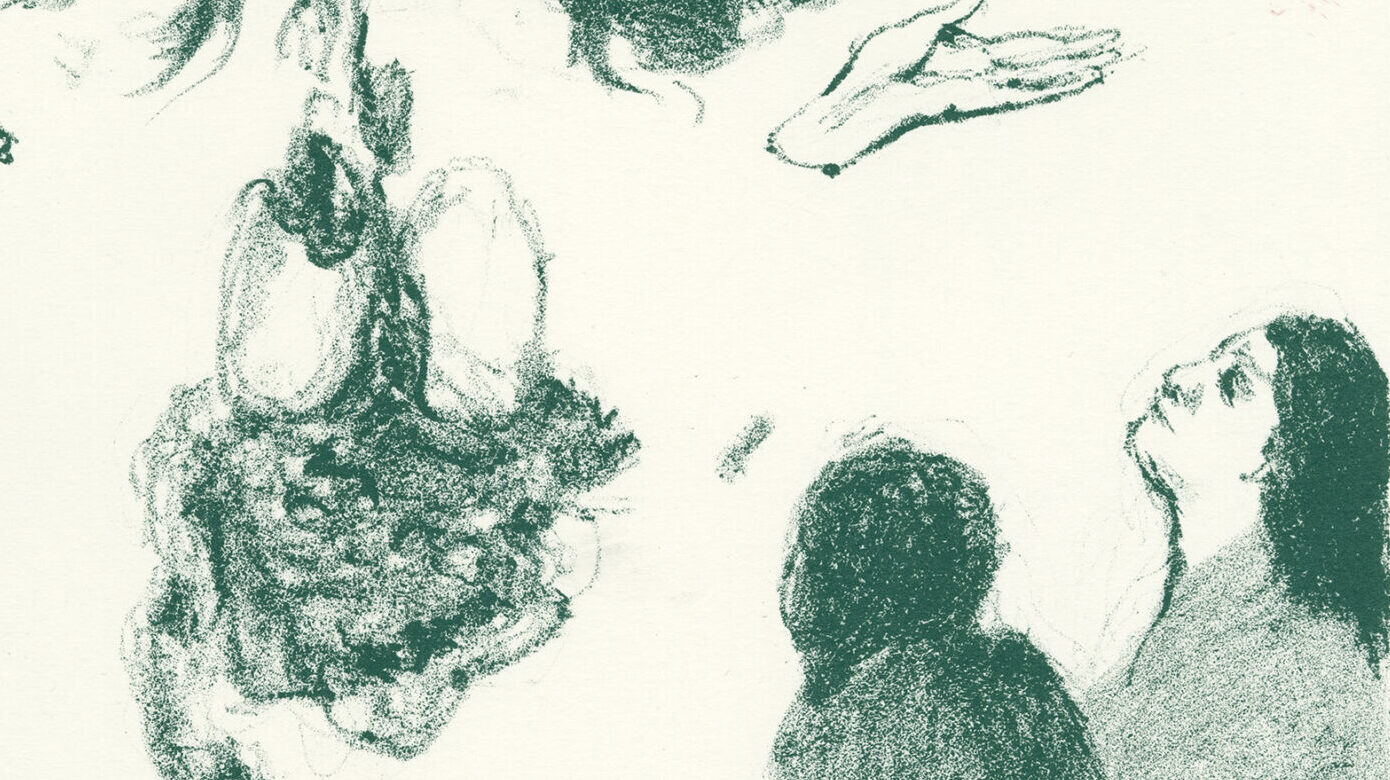

We knew our hands were not aligned. One of our hands was flatter with wider and shorter fingers. Hands perfect for digging holes into the earth or picking acorns from the ground and holding hordes of them. The other set of hands was more narrow and moved like they were attempting to grasp onto air, which meant they were always dropping things out of the fingers that were slightly too bony.

We compared our feet next. Our feet were already bare, the rule that tied our houses forbidding shoes indoors. One of us never had to bend down to brush the floor with their hands, possessing feet that were always pushing the surface with great gripping toes that could be used to pick up trash from the floor. The other had feet that barely touched the ground, with arches too high and one nubbed toe to press grains of rice into soil.

We continued to move upwards, comparing shins, which were more or less the same length, then our mismatched knees, and then the mark. We had never revealed them to other, and even though we shared as much as we could within the walls of school, we never discussed the ways our bodies worked. We assumed our bodies matched as much of the rest of us did and weren’t worth discussing.

Our mothers told us to hide the markings. Forcing us into long pants and skirts, even on the hottest days when musty rivers poured down our butt cracks and our hair tangled in the fury of the air’s steam. The markings of demons needed to be hidden, they said.

But demons wore horns on their heads and had tails extending from their spines. Our markings showed who we belonged to.

We must have been born mushrooms or oranges in our past life, one of us said. That’s why our bruises are always breaking through our skin when we hold one another.

To think we could be cleaved from another living organism and find ourselves here, where we could not be apart.

Our marks were moving and malformed, some days showing the sprawling scrolls of the night-sky zodiac up our thighs. Other days we could only make out the jaws of a crocodile, crushing the head of a horse. We tried to note the patterns and the happenings in the world to make sense of our marks, but we couldn’t find the portal to step through that would provide us an understanding. But we found the missing pieces within each other.

That night, we pressed our knees together so one skinny knob of bone kissed the fleshy heart of the other’s knee. Matching our legs so our markings could meet and swarm. We watched as a moving mural unfolded between us. The crooked teeth of the houses in our neighborhood, linked together with the braces of hand-staked fences that would keep the pack of wild coyotes out of the dignified lawns and away from the domesticated dogs that filled our homes. As the shadows of our legs shifted, we saw our mothers. One was at her altar, attempting to open the portal to the forgotten place, where those who were left behind, whose names were erased existed. Her summoning skills were limited to her children, and the door to the ancestors remained rigid and locked. The other was fleeing the smoky dragons of the cooking shed to smack our brother for being too wild in the neighborhood.

We watched as the scenes changed and stayed joined together, reveling in how the scenes moved and altered as the figures of our families blended and transformed and shifted. Their figures blurred into the backyard dogs and into the smoke dragons until every shadow that formed between our legs had multiple limbs and tails, until our birthmarks settled back into our own bodies as we collapsed in sleep, tangled together.

We took to escaping class with unsanctioned bathroom breaks to both escape the boys and discover what we could create together. We snuggled together in stalls after getting on our hands and knees to make sure each station was cleared of legs and people peeing. When we knew it was safe, we would peel up our dragging pant legs and skirts and push our knees together. A relief of skin when we no longer had our hair pulled or breasts prodded and shoulders slapped or bellies pinched by the boys who still delighted in our torture, as they still couldn’t claim the dirt kingdom we had built. But this was the skin we wanted for ourselves. This was ours and we could decide how we were touched.

There was never enough time to watch the stories finish between the panes of our flesh. Sometimes we only had seconds to see what our knees could make out. We would see fragments of the clouds that decorated our neighborhoods. We saw tigers and dragons chasing one another’s tails until they both consumed themselves completely. Some days, emergences of weather predictions decorated our thighs and we came to school the next day with black garbage bags in our backpacks to form makeshift raincoats at recess, which allowed us to be the only ones outside and which let us rebuild our nation of bunnies, perfect to structure in the mix of mist and mud.

Each time we got to be alone and less dressed, we were able to explore more, until our bodies felt completely mirrored. One’s hunger was the other. We could feel when the other’s mother slapped one of our heads with a shoe. We could predict where our bruises would rise and what shapes they would take. One’s upper arm bore a mark that looked like a drum but the other’s empty arm could still feel its tenderness. When the boys pulled at us, it made the aches set in even deeper. Our torture was doubled, but knowing we were never alone in our feeling was a freedom.

Yet our minds were wrapped around one another. Though our thoughts were still our own, each idea circled around how we could get closer. We thought of ways to skip class without getting caught. How we could extend our bathroom breaks by plagiarizing doctor’s notes. While the obsession kept us from looking at the kaleidoscopic colors of sky and fields, the time we could be next to one another was such a relief it wasn’t too bothersome. But we still stretched for more.

The hunger fueled us until one of us finally lowered our head while we were stuffed in the bathroom stall and contorted to taste our birthmark. The tongue did not reach its target and instead fell through and did not taste sweat, but felt the empty space of air and sensed a lingering of incense. The other followed as we fell into our birthmark.

Our bodies reemerged into a tumult of darkness where we breathed in the cloying smoke that covered the room. We could make out smoldering piles of money. A snap rang through as we adjusted back to our own flesh. I could no longer feel her. The pain of my own bruises burst forth and my flat feet slammed against the earth of this realm and reverberated through my bones, leaving me tremoring. I checked myself to make sure I came out with all of my toes and teeth. Each part of myself felt firmly glued to my body. It was always mine, but it had been forgotten between the slaps of my parents and the prods of the boys. The decisions, which were camouflaged as belonging to me, never offered the balm of agency, and each time I followed someone else’s desires, I felt myself swallowed until the distinction of my own fingertips vanished in the acid of their orders. I wasn’t allowed my own door and was monitored when I got dressed. How could a person like that have a body? The only relief I felt was when she was next to me and I knew I wasn’t solitary and single.

I reached out to grab her hand, lost in the darkness, in need of some shape of guidance. And I felt her, fleshy inside of my own grasp. She pulsed my palm. I took steps slowly, my feet unsure as I trenched through the dust of ash. My stride no longer matched hers like it did above, which made my knees clumsy. I saw the mounds of burning cars and electronics. Each one was unclaimed. I continued to navigate the unfolding region as each step revealed more. Tatters of old photos came into focus, each with faces that I could make out. One had her ears. One had my nose. My smile was reflected in the paper face of another.

“We were the portal,” she gasped.

I looked around us. Though I had no living memory of this place, the whispers that shaped my dreams of longings of those whose names had been forgotten bore into my bones with a comforting familiarity. This was the place called forth in my mother’s prayers. I had fallen into the land of our ancestors, the ones whose altars were never created the way they needed to be. The remains of the wandering souls who could not find home. I was in the ash of their bones and offerings. Inside the rotting flowers that were left one final time for a grave that was never cleaned again. The land her mother was always seeking to open with new configurations of her altar and prayers. This is where I found my own body and her own body.

“Did she tell you what happens to the living who get stuck here?” I asked.

“No. She didn’t talk about it at all. Just that she was trying to open this world. She felt bad for the missing spirits. All of whom couldn’t find their way back because the voices to lead them home got confused or were never given their proper rites.”

The air smelled sweet and the ash was soft. The glow of the incense felt warm. I stretched my free fingers, splaying them out to palm through the smoking air. Feeling the relief of stretch. The freedom of my skin. How her heat radiated into me, not in the way where I could feel her pain reflected into my own muscles, but one that felt like the glow of summer sipped into me.

“What about the living that stay?” I leaned down, seeing an orange too ripe and bright for the surface. The pocked peel glimmered.

“I don’t know.”

I unwrapped the thin skin of the orange and took a bite of it whole as its juice slipped from my fingers and left its markings on my chin.

“Maybe we can be the first.” I pressed the orange to her lips.

She sucked at its flesh and ate. Her face radiant in the reds of embers, she swallowed and broke into a smile.